The attainment gap - a look behind the stats

Topic: Corporate parenting, Education, Foster care, Local authority, Looked after at home

Author: Linda O'Neill

Two important education documents arrived in June - the Educational Outcomes for Looked After Children 14/15 statistics, and Delivering excellence and equity in Scottish Education: A delivery plan for Scotland.

The statistics are published annually and show how our looked after children are doing at school, in terms of attendance, exclusions, and qualifications. The new delivery plan is a bold and ambitious blueprint for improvement within Scottish education, focusing on how to close the attainment gap.

From our perspective at CELCIS, these two publications talk to each other well. For without data it’s difficult to make good plans, and without good plans we’re unlikely to see improvement in looked after children’s attainment; which is so critical to ‘closing the gap’ more generally. Every school and local authority should be using the data at their disposal to drive continuous improvement, not satisfied until they’ve worked out how to provide every child with the high-quality education that they have a right to.

What do this year’s statistics tell us?

Unfortunately, it’s a similar story to previous years. Some indicators continue to show small improvements for looked after children on a year-on-year basis, and the success of some groups of looked after children is impressive. But taken as whole population, there is still an unacceptable and unjustifiable gap between their educational experience and those of most other pupils.

Big strides were made in 2014-15 in closing the attendance gap. Overall, looked after children’s attendance, at 92%, compares well to a national average of 94%. The devil is in the detail though. Children looked after at home, who make up 20% of all looked after children at school, only average 81% attendance. This is an important factor in explaining why the attainment for this group of children is so much lower than the national average - children need to be at school in order to learn, and if we only provide a few hours of education to a child each week, we must take responsibility for the educational (and therefore life) outcomes which follow.

While 98% of all school leavers achieve at least one qualification at SCQF 3 (equivalent to a foundation level standard grade), only 86% of looked after school leavers do. And just 63% of leavers who were looked after at home manage this level. We already know that one of the reasons for this is looked after children aren’t at school as often as all other children, but these low attainment figures also reflect the fact that three-quarters of looked after children leave school at 16, compared to just over a quarter of all learners. Perhaps it’s no surprise then that 14% of looked after children leave school with no qualifications at all, compared to only 2% of all school leavers. Is it right that we let so many young people embark on the journey into adulthood without the basic qualifications necessary for employment or further education? The longer children are in education the more chance they have of attaining qualifications and of finding the approach to learning which works for them. The statistics show that the attainment of a looked after child improves the longer they stay at school. This raises the question of whether we should be raising the ‘education’ leaving age from 16 to 18 (as they have in England), providing all of our young people, but particularly those who are most vulnerable, a longer window in which to achieve?

A sense of stability

However, attendance and an early leaving age aren’t all that contribute to the attainment gap. Exclusion has a significant part to play in understanding the ‘why’ in the figures. Over the past seven years there’s been a reduction in exclusions across the board, but the fact remains that if you’re a looked after child in one of our schools then you’re eight times more likely to be excluded. This not only impacts on learning in the classroom, it excludes children from, social, cultural and extra-curricular activities. Whatever the impression some give on a day-to-day basis in school, and despite the behaviour which some display, looked after children are among the most vulnerable people in our society. Isn’t it time we began to ask ourselves seriously how ethical it is to use exclusion as a sanction for such people? Yes, in certain circumstances it is necessary to take action to protect a child from causing harm to themselves or others. But every time we exclude a child from school, we are putting another brick in the wall which they must climb over in order to succeed.

Children in foster care and those who have the fewest placement changes over the year fare better. That intuitively makes sense. Having a consistent family home with a sense of permanence and stability will help children achieve in school. As a system – not just education but the children’s services system, we need to figure out how to provide children with this sense of permanence and stability within education. School is a really important protective factor for children, and much more effort needs to go into ensuring that, as the rest of their life is in flux, we keep their education a safe, nurturing constant.

Moving on from school

By doing this we’ll make an impact, not just on school achievement and attainment, but also lay the foundation for post-school progression. 2014-15 saw the gap grow between all children and looked after children in terms of immediate post-school destinations (employment, education, and training), and the sustainment of those destinations. The Scottish Government has committed to closing this gap by 2021 in their response to the Wood Report. But, the challenge of this is illustrated in the statistics which show that only 77% of looked after children compared to 93% of all children secured a positive post-school destination this year, and of those only 69% were still in that destination nine months, later compared to 92% of all children. What particularly concerns me is the numbers of school leavers entering higher and further education increased or remained consistent last year, but dropped for looked after children.

This is in a year when we’ve seen a significant shift in the policy landscape, supposedly designed to deliver improvements for looked after children. Corporate Parenting duties now apply to all colleges, universities, and Skills Development Scotland, and the Developing the Young Workforce and Scottish Funding Council’s widening access programmes are well underway. Is it too soon to expect to see positive change for looked after young people? If so, how long is it going to take? And what does this mean for delivering the new plan?

The missing link

While the Scottish Government’s delivery plan is not specifically aimed at closing the attainment gap that exists for looked after children, it has a large focus on reducing the gap associated with poverty and disadvantage. Looked after children are a group that face multiple challenges and disadvantages.

The plan for closing the gap is bold and ambitious, and I’m pleased to say, aspirational. On the first page though it sets out no less than nine separate policies or agendas aimed at helping our children, families, and communities. They are all founded on a solid evidence base - the ‘why’ and the ‘what’ of the challenges we face. This is only half the answer though, literally.

What research also tells us, more clearly all the time, is that without good, solid implementation even excellent programmes or supports will only achieve around 50 – 60% of their desired outcomes. It’s almost counterproductive to spend time, money, and resource on setting out the rationale for why and what we need to change, without attending to the ‘how’ (particularly when the document is called a ‘Delivery Plan’). I would argue that this has been, and could continue to be the missing link in closing the attainment gap for our children.

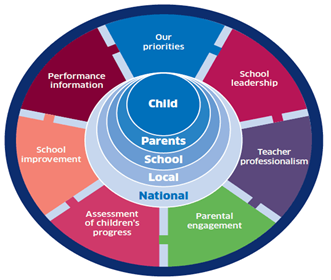

This plan has the opportunity to take the ‘why’ and the ‘what’, combine it with the lessons we have learned from past policy roll outs, and bring it all together with a good implementation strategy. If we pay attention to leadership at all levels, understand and support our organisational systems, and ensure that we’re investing in our practitioners with ongoing support and coaching, then Scotland will be well positioned to achieve the aspirations set out in this document. Without that clear-eyed and hard-headed focus on implementation, this all risks becoming an expensive, essentially bureaucratic exercise, with the potential to actually get in the way of the improvements it aims to deliver.

But if we pay proper attention to the missing piece of this ‘pie’, then it’s just possible that within two to four years we could be writing about how we started to really close the attainment gap.

Have a look at our education pages for more on the work of CELCIS.

The views expressed in this blog post are those of the author/s and may not represent the views or opinions of our funders.

Commenting on the blog posts: sharing comments and perspectives prompted by the posts on this blog are welcome.

CELCIS operates a moderation process so your comment will not go live straight away.