Glossary

Some words or phrases have a specific meaning within the context of Active Implementation or refer to particular theories or practices. Definitions and explanations can be found on a specific glossary document when the word or phrase is {highlighted like this}.

Effective Practices

The WHAT – involves reaching consensus and developing a well-conceived view about what exactly is to be implemented, and ensuring that the innovation (e.g. a programme or a practice that varies from the standard or is new), or the effective practice, is described in a clear and usable manner. Effective practices should therefore be teachable, learnable, doable and assessable.

This section describes the rationales and the vision for change in Dundee, providing an opportunity for people interested in strengthening early support and intervention, as well as the voice of children, young people and their families, to find out more about the practice changes achieved through the ANEW programme.

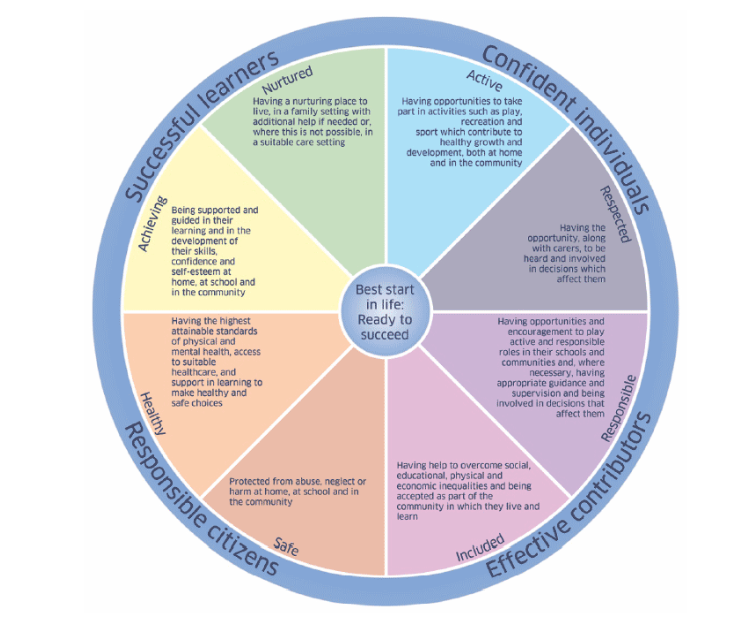

Through a rigorous initial exploration of the local contexts in Dundee, Inverclyde and Perth and Kinross, an implementation gap between policy and practice was found in relation to the Scottish Government’s ‘Getting it Right for Every Child’ (GIRFEC) framework. As a result, all three local authority areas involved in ANEW identified the need to strengthen the implementation of GIRFEC as the key mechanism for responding to early concerns and ensuring that children and families get the support they need, when they need it.

Exploration is one of the stages of implementation that cannot be skipped, in the ‘How’ section you will read more about how we supported our local partners to explore their systems.

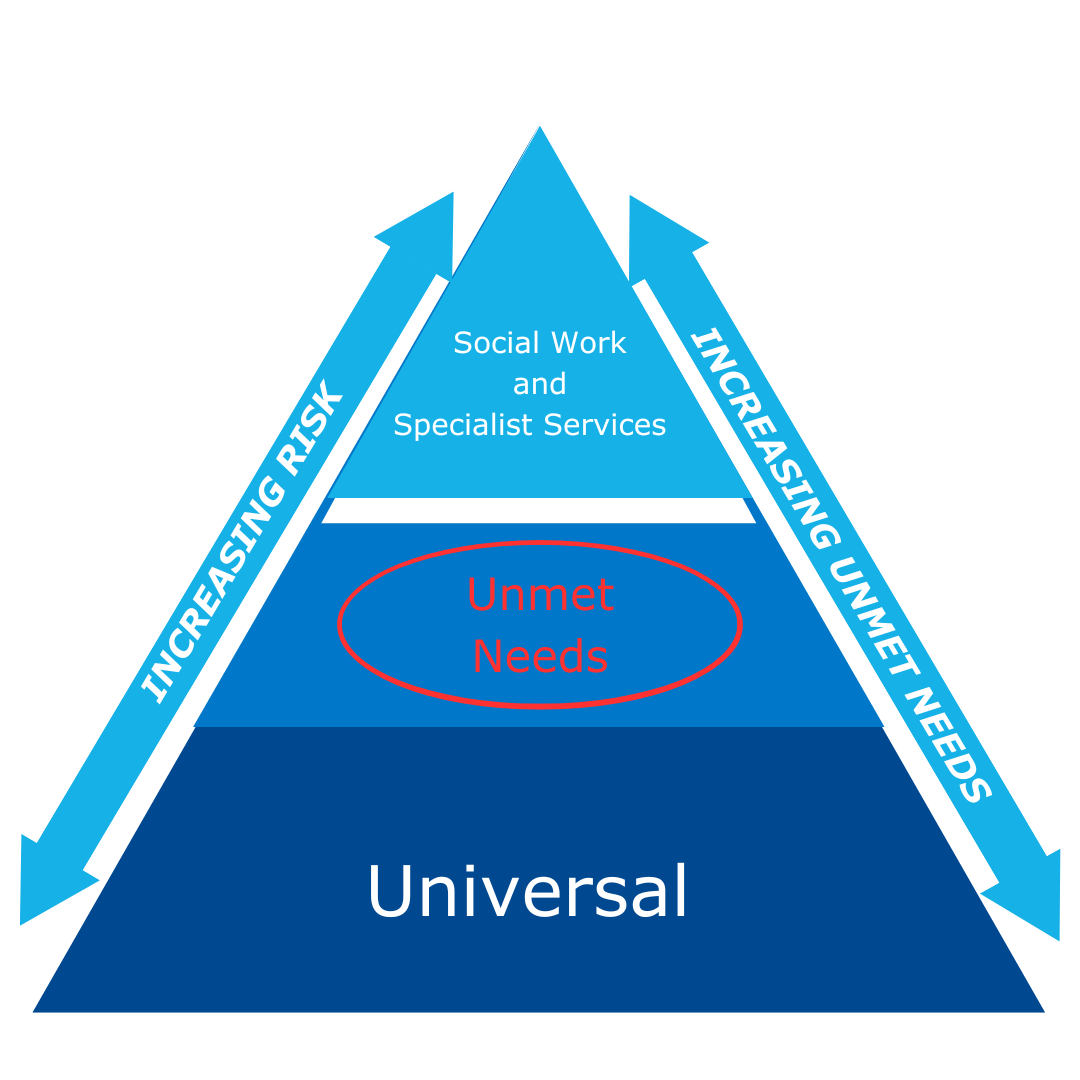

In Dundee, the extensive whole system exploration found that some families had needs below the threshold for specialist services or statutory measures, but which were not met through the universal services’ pathways. Left unmet, those needs would often increase, leading to concerns escalating and families having to navigate greater challenges. The Dundee implementation team and senior leaders sought to ensure that those lower-level concerns were noticed and responded to at the earliest opportunity, which led to a vision for change where:

- Families are seen as experts on their own lives, with people having an opportunity to share and have their voice heard as part of any planning process and in helping to identify what supports they need and when they need them;

- Universal services (e.g. health visiting, education practitioners) are considered to be well placed to build relationships with families, so that unmet needs can be understood and responded to in a timely and coordinated way;

- Relationship and strengths-based practice underpin any decision-making processes about a child’s or young person’s life, as this values the resources and capabilities of each family, builds trust between families and practitioners, empowers families and strengthens their resilience;

- Early support for low level unmet needs is available to all, helping families to sidestep challenges before they occur and having a positive impact on their health and wellbeing.

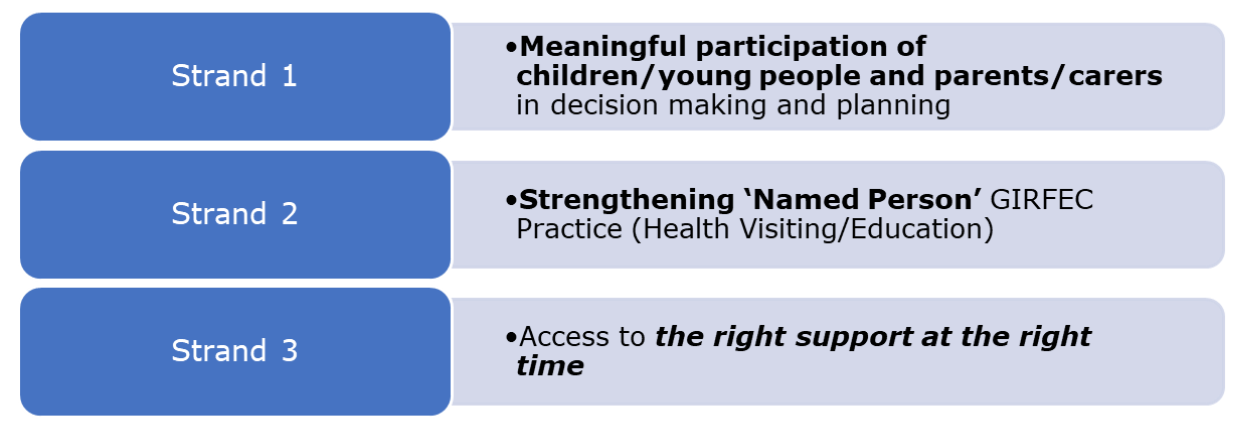

This vision for change led to three strands being identified as central to Dundee’s change design.

Strand 1

The first strand focused on ensuring the meaningful participation of children, young people and parents or carers in decision making and planning through a rights-based approach.

What was the challenge?

One of the main challenges identified in the Dundee exploration was that child and parent voices were not being widely heard, both in terms of preparing for and during the meetings convened as part of the Team around the Child process. This meant that anxiety was felt by all meeting participants, impacting on the level of participation and quality of decision making.

What was the change in practice?

The effective practice developed is rights-based and is attended to through changes to how Team around the Child meetings are held and adapting the ‘Meeting-Buddy’ approach developed by Children 1st (initially used in Child Protection settings) to be used for early intervention in the Team around the Child process. The aim of the ‘Meeting-Buddy’ approach is that children and parents become equal partners within the decision-making process.

A Meeting-Buddy is an adult (but not the chair of the meeting) who is trained, coached and enabled to support the voice and participation of children and parents or carers, in the manner that each child/parent/carer is most comfortable with.

A Meeting-Buddy provides support not only during a planning meeting, but also before and after, in recognition that participation is not a one-off event, but a process that requires time and support for the child to understand the process and their rights, decide how they can and wish to engage in the process, and understand the outcomes and what will happen next.

Who was involved in the change?

The change was developed gradually, through iterative testing in four sites – three primary schools and a nursery. CELCIS and the Dundee Implementation Team worked closely with the site teams to introduce elements of new practice, study their impact and collaboratively decide adjustments before repeating the testing cycles. The effectiveness of the changes was determined based on observation of practice and feedback of children, parents, carers and practitioners involved in Team around the Child meetings. A key role in adapting the Meeting-Buddy approach to early intervention was played by Children 1st staff who were members of the Dundee Implementation Team and who provided expert advice, training and coaching on supporting the voice of children, parents and carers.

What was the impact of the changes?

Important changes were introduced in relation to the set up and chairing of Team around the Child meetings to reduce anxiety, and make them feel less intimidating and accessible to families:

- Rather than leading with professionals speaking, the meeting structure changed to allow the child's or young person’s views to be expressed first, followed by the views of parents or carers, and then of professionals. This placed the voice of the child or young person and their family at the heart of the meeting from the very beginning, setting the tone and encouraging engagement and participation;

- Previous meetings had used the headteacher’s office or more formal ‘conference style’ meeting rooms, which could feel intimidating to children and families. To improve this, more informal meeting rooms were set up and attention was paid to creating a welcoming environment and minimising interruptions. The arrangements differed, but some examples include setting up a space for preparing hot drinks, having accessible GIRFEC visuals and information materials on walls, setting up chairs in a circle around a coffee table, shifting the power balance away from something that felt like a meeting solely for professionals to a meeting that was focused on helping children and families. This helped to reduce feelings of anxiety and defensiveness in children, young people, their parents and carers, and put a focus on providing support to engage in the meeting;

- There were previous examples where professional assessments were presented at the meeting without being discussed or shared with the family first, thus it became important to ensure that there are ‘no surprises’ in the meeting, and that the child/young persons and the parents or carers are informed in advance of the meeting about what professionals plan to share at the meeting. This helped to reduce anxiety and defensiveness, and supported everyone to feel informed and prepared for the meeting;

- Discussing what works well for the family and the progress made, to ensure that the meeting is strengths-based, builds on the positive progress, and empowers the family;

- Checking in, regularly throughout the meeting, with the child and the parents or carers, to ensure their understanding of the meeting and, moreover, that they are engaged as equal partners throughout the meeting;

- Writing up the Child’s Plan in the meeting, so that it is visible to all (such as on Smart Board, Flipchart or A3 page) and that all meeting participants can contribute to and understand the Plan;

- Giving the Plan to the child/young person and the parents/carers to take away at the end of the meeting, which reinforces that it is their plan, reduces the anxiety around the content (ensuring that there are ‘no surprises’ after the meeting either) and provides an accessible list of next steps.

Strand 2

The second strand focused on providing support to practitioners undertaking the function of named person, a need identified through the whole system exploration that took place in the first stage of the ANEW programme.

Find out more about the named person role and function

Within the GIRFEC approach, the support of a named person is available to all children, young people and their families.

Although the role of the named person may be known by other names across Scotland, the core functions are similar; for example, acting as a central point of contact for children, young people and parents or carers, providing families with information, or helping them get the support they need, if and when they need it.

The named person functions are performed by different practitioners depending on the age of the child or young person. The functions are usually performed by: health visitors or family nurses and early years education practitioners during early childhood; head teachers, depute head teachers or other promoted teachers, in primary school settings; and, in addition, guidance teachers, in secondary school settings.

You cand find out more about the Scottish Government’s policy on the named person role here.

What was the challenge?

Whilst there was already a degree of alignment, some of the processes and functions introduced through GIRFEC have extended the traditional roles of health and education practitioners (e.g. chairing a Team around the Child Meeting, coordinating needs assessment etc.). Our exploration of the system found that the health visiting, early years and education workforce had responded well to the complex asks made of them, but questions persisted about the alignment with other asks derived from a rather complex policy landscape. Moreover, important gaps were highlighted in relation to defining what ‘high-quality’ GIRFEC practice looks like. Active Implementation tells us that such issues cannot be overlooked, because practice must be well defined (or operationalised) to help practitioners to have clarity in their role and become confident and competent in their practice.

What was the change in practice?

The development of the practice profile was focused mainly on GIRFEC, but it also incorporated the skills, competencies and behaviours associated with a range of other key national education and health policies and developments [‘?/Find out more’ button/ accordion box]1.

Who was involved in the change?

An iterative and collaborative approach was taken when developing the practice profile – CELCIS and the local Dundee partners facilitated workshops and invited the submission of comments on the working drafts involving NHS Tayside health visitors, family nurses, team leads and managers, and Dundee City Council teachers, educational psychologists and managers throughout this process.

The resulting GIRFEC Practice Profile for Health and Education professionals holding the Named Person function was published online by Dundee City Council, in September 2021. It was officially launched in the same month, during Dundee’s multi-agency GIRFEC Learning Event, which included a series of interactive sessions with approximately 350 staff with named person and lead professional functions.

What was the impact of the change?

The practice profile has been well received and considered a valuable resource by those involved in its testing and subsequent use.

[to check and hopefully include quote/video on the practice profile]

Strand 3

The third strand focused on supporting the local referral system used by practitioners in a named person role (and not only) for triaging and linking the identified needs of children, young people and their families with public and third sector services.

This has been attended to through developing the ‘Fast Online Referral System’ (FORT) in Dundee, supported by a partnership between the voluntary sector, Dundee City Council, Health and other partners. FORT maps services across Dundee, hosts an online service directory and provides a triage referral tool for practitioners.

Only the first two strands were directly supported by CELCIS. For more information about FORT, visit the website: www.supportandconnectdundee.org

Overall, the approach developed in Dundee is rights-based, being rooted in the United Nations Convention on the Rights of the Child (UNCRC). Moreover, the publishing of The Promise (2020) confirmed the relevance and importance of the Dundee’s change design, which strongly aligns with the Promise’s foundation that ‘children must be listened to and meaningfully and appropriately involved in decision-making about their care, with all those involved properly listening and responding to what children want and need’ (The Promise, 2020, p. 9).

Key learning:

- The greatest leverage point for addressing neglect and enhancing wellbeing was identified as meeting children and families’ needs earlier and increasing the capacity of universal, preventative and early intervention services to respond at the level below formal statutory measures.

- Participation of children and parents or carers in planning and decision making is a process, with the preparation stage vital. Meaningful participation of children and parents or carers requires disrupting the power imbalance between professionals and children and parents or carers, as well as amongst professionals.

- Some of the functions introduced by GIRFEC, especially in relation to early intervention and prevention, require supports to be put in place to help practitioners gain clarity of what is expected of them. Functions cannot simply be ‘layered on’ without paying attention to aligning and integrating them into daily practice.

- Embedding new ways of working requires defining or operationalising the types of practices which are effective in engaging and meeting the needs of children and families.

- GIRFEC named person practice sits within a layered and complex policy landscape, which made the crosswalk with other key national education and health policies and developments a must, in order to understand the similarity, complementarity, overlap and difference across them. A similar approach is recommended when operationalising any other practices.